9000BC - 500AD

People have lived on Ardnamurchan since Mesolithic times, over 10,000 years ago. When people first arrived here, they were nomadic, moving along the coast in small groups and never staying in the same place for long. At this time, they lived in caves or simple shelters, were hunter-gatherers, and had simple tools made from bone, antler or stone.

Later in the Neolithic era, around 6000 years ago, people started living a more settled lifestyle, building more permanent homes using wood, and farming the land. They grew basic crops such as oats and barley, and kept animals, including cattle, sheep and pigs.

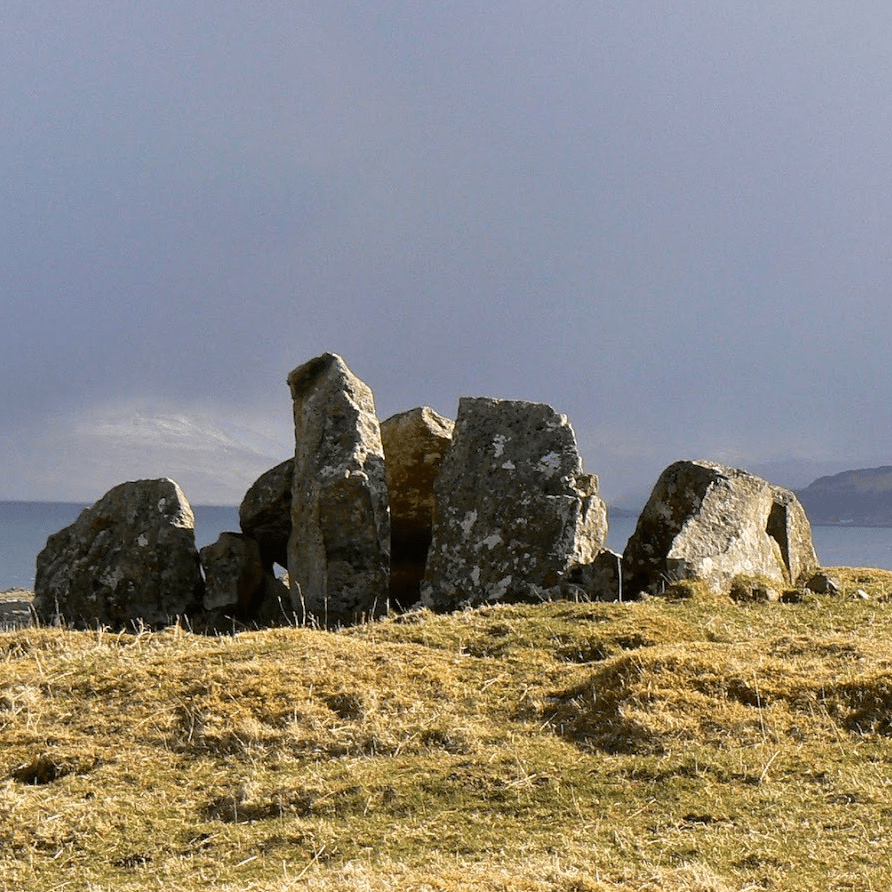

You can see evidence of these Neolithic people on Ardnamurchan today. There are stone structures, such as burial mounds, cairns, and standing stones at Greadal Fhinn, Camas nan Geall and Swordle. These were built thousands of years ago as part of some form of religious observance, suggesting a belief in an afterlife.

Archaeologists have also found tools, ornaments and weapons from the Bronze Age and Iron Age on Ardnamurchan, dating from around 4000 years ago. Around this time, people wore clothing made from wool which they spun and wove into skirts, tunics, kilts, cloaks and hats. With the Iron Age, a wave of European settlers arrived on the peninsula, now known as the Celts. Celtic life revolved around tribal units led by chiefs, and they also developed specialised classes of people, such as priests, farmers and tradespeople.

You can find Iron Age features on Ardnamurchan, including stone fortifications, called duns, and settlements built in lochs, called crannogs.

Later in the Neolithic era, around 6000 years ago, people started living a more settled lifestyle, building more permanent homes using wood, and farming the land. They grew basic crops such as oats and barley, and kept animals, including cattle, sheep and pigs.

You can see evidence of these Neolithic people on Ardnamurchan today. There are stone structures, such as burial mounds, cairns, and standing stones at Greadal Fhinn, Camas nan Geall and Swordle. These were built thousands of years ago as part of some form of religious observance, suggesting a belief in an afterlife.

Archaeologists have also found tools, ornaments and weapons from the Bronze Age and Iron Age on Ardnamurchan, dating from around 4000 years ago. Around this time, people wore clothing made from wool which they spun and wove into skirts, tunics, kilts, cloaks and hats. With the Iron Age, a wave of European settlers arrived on the peninsula, now known as the Celts. Celtic life revolved around tribal units led by chiefs, and they also developed specialised classes of people, such as priests, farmers and tradespeople.

You can find Iron Age features on Ardnamurchan, including stone fortifications, called duns, and settlements built in lochs, called crannogs.

Meet Pat...

Pat is here to help you understand what life was like on Ardnamurchan during this time. Pat is one of the first farmers on the peninsula and has lots to tell you about what life was like for them!

Read stories told by Pat below, and find out what life was like for her …

Camas nan Geall

We hunt and gather our food, making our own tools such as arrows from beach flints to hunt animals from the land and seals and fish from the sea - it’s handy living on the coast! We also eat lots of native plants and gather shellfish, and started growing crops and farming too.

A little further west along this coast there is an Iron Age fort - it’s a great look-out post for boats arriving, but it's easy to miss if you're not looking for it!

Go to Camas nan Geall

Greadal Fhinn

We bury the dead differently to you - or I imagine so anyway! We leave bodies out in the open, away from where we live and work, and they are left to decompose or be eaten by animals. We then collect the bones and put them in the tomb alongside the bones of others. Different parts of bodies are placed in the tomb in different ways, taken out of the tomb, put back in and rearranged over time. Doing this helps us to blur the distinction between individuals but also of the past and the present.

Greadal Fhinn is the most southerly example of a Hebridean cairn, with two burial chambers remaining - a small central 'cist' cairn, and a larger passage chamber, which was dug into the site later on.

We chose this as a place for ritual and burial because of its prominent position in the surrounding hills and Kilchoan skyline. We come here to connect with our ancestors, the landscape and each other.

You will still be able to see stone structures from the Neolithic Age at Greadal Fhinn, Camas nan Geall and Swordle - we built them to last!

Go to Greadal Fhinn

Sanna

There is a fort built here that looks out to sea - it’s the perfect vantage point to spot enemies arriving and scare them off with iron-tipped arrows!

When people first arrived on the peninsula they set up camp here - and you can see why; it’s a beautiful spot and great for gathering food from the sea - especially shellfish suppers, my favourite!

Go to Sanna

Swordle

The cairn here known as Cladh Aindreis is an important place of connection and ritual. It’s where the first farmers at Swordle are buried, and has been used as a place of burial over hundreds of years in many different ways. In the past people would rearrange bones in the burial chamber over the years, mixing bones from different times and rearranging them to make connections through generations. More recent burial rituals involve cremation and beakers which are made from clay to bury people's ashes in.

Go to Swordle

Early Medieval

500 AD - 1100AD

Two thousand years ago, the people living on Ardnamurchan were a branch of Celtic Britons known as the Picts, whose language is still a mystery today. They were called 'Picti' by the Romans, meaning 'painted people', because of their custom of body painting or tattooing. Later, by the sixth century, many Dalriada Gaels from Ireland arrived, whose Celtic language is the origin of the Scots and Irish Gaelic spoken today. The Picts and Gaels began to merge as Gaelic influence and culture spread, until eventually Pictish power on Ardnamurchan gave way, and the kingdom of the Gaels stretched from the Western isles to the Eastern coast.

Saints from Ireland visited Ardnamurchan during this period; St Finnan, St Columba and St Comghan. The memory of these visits lives on in local place names.

The Vikings, who sailed to Ardnamurchan as raiders, stayed here, becoming farmers and steadily integrating into the population. The most obvious evidence of their time here comes from the names they left behind, such as Mingary and Greadal Fhinn.

Saints from Ireland visited Ardnamurchan during this period; St Finnan, St Columba and St Comghan. The memory of these visits lives on in local place names.

The Vikings, who sailed to Ardnamurchan as raiders, stayed here, becoming farmers and steadily integrating into the population. The most obvious evidence of their time here comes from the names they left behind, such as Mingary and Greadal Fhinn.

Meet Erik...

A Viking farmer living in Ardnamurchan during this time, he has many stories to share, about settlement, the Irish saints and the warrior buried in Swordle!

Read stories told by Erik below, and find out what life was like for her …

Camas nan Geall

We carved three crosses and an image of a dog into the tallest stone we could find - they help us to pray and mark this place out as sacred.

St Columba, the Abbot of Iona, visited us here at Camas nan Geall. He’s most famous for establishing the Monastery at Iona and bringing Christianity to Scotland, and I heard he has performed miracles all around the West Coast! When St Columba visited Camas nan Geall he struck his staff into the hillside, creating a fresh water source for the baptism of a sick baby. It was amazing to see the frail baby grow strong again and thrive, thanks to St Columba's healing powers. To this day the well that St Columba created is still flowing; you can see it on the hillside on the Ardslignish side of Camas nan Geall.

Go to Camas nan Geall

Greadal Fhinn

I heard that this site is the final resting place of the Viking, Ketill Björnsson - a Norse king from the 9th century - nicknamed Flatnefr/Flatnose!

Us vikings have certainly left our mark on Ardnamurchan - many of the names you'll see around such as ‘Mingary’ and ‘Greadal Fhinn’ come from us.

Go to Greadal Fhinn

Swordle

He was buried in the traditional way befitting such a warrior. Into the boat alongside his body was placed everything he would need for his journey - most importantly his sword, axe, and a whetstone to keep them sharp, his drinking horn, and brooch.

We arrived as Viking raiders and stayed here ever since, integrating with the Gaels and Celts. We farmed too - I grew oats and barley, and kept cattle, sheep and pigs; more than enough to keep me busy!

Go to Swordle

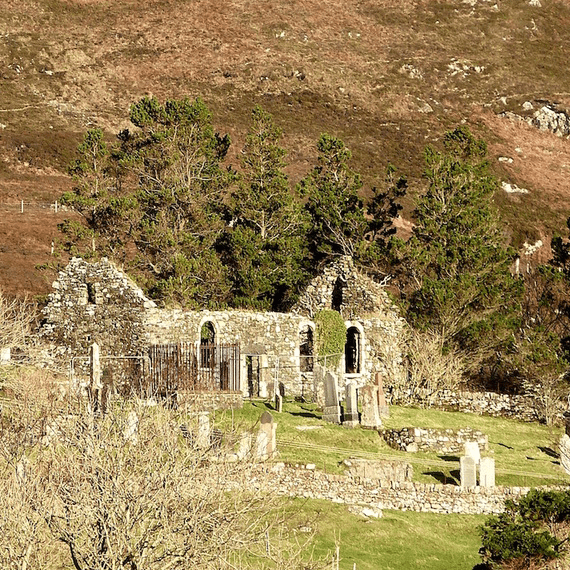

Kilchoan Old Parish Church

We call the village ‘Kilchoan’ because of this church: The church (Cille) was dedicated to Saint Comghan (Chomhghain).

Go to Kilchoan Old Parish Church

Time of the Clans

11th Century - 1745

As the population grew on Ardnamurchan, people settled into groups of families that we now know as clans. Clans had a chief who took responsibility for the clan, and a tacksman collected rent for the chief. When needed, men were required to fight for their clan, which they did wearing their clan tartan and kilts on the battlefield. Many people on Ardnamurchan were on different sides of the Jacobite uprising and other conflicts, and afterwards lived close together on the peninsula.

Underpinning everyday life in a clan was the concept of duthchas, a concept of being rooted and connected to a particular place by family history, collective heritage, and ancient lineage.

People at this time lived in single-storey buildings made of local materials, including wood, turf, reed, heather and, later, stone – of which the two-roomed blackhouses are the best known. Land was fertilised for crops with bracken or seaweed and could be very fertile. Areas of farming land were allocated to different families by drawing lots on a regular timetable so that the best land changed hands regularly and was shared fairly. There was also common grazing land, which everyone in the township used for their cattle and sheep.

In summer, many women and children stayed in shielings on the common land and made products such as cheese, while men worked the arable land for crops of barley, oats and, later, potatoes. People also ate shellfish collected along the shore and fish from the sea.

Underpinning everyday life in a clan was the concept of duthchas, a concept of being rooted and connected to a particular place by family history, collective heritage, and ancient lineage.

People at this time lived in single-storey buildings made of local materials, including wood, turf, reed, heather and, later, stone – of which the two-roomed blackhouses are the best known. Land was fertilised for crops with bracken or seaweed and could be very fertile. Areas of farming land were allocated to different families by drawing lots on a regular timetable so that the best land changed hands regularly and was shared fairly. There was also common grazing land, which everyone in the township used for their cattle and sheep.

In summer, many women and children stayed in shielings on the common land and made products such as cheese, while men worked the arable land for crops of barley, oats and, later, potatoes. People also ate shellfish collected along the shore and fish from the sea.

Meet Mac...

He is a Clan Chief and has lots to tell you about farming, clan disputes and what the settlements were like on Ardnamurchan.

Read stories told by Mac below, and find out what life was like for her …

Achnaha

In the 1720s-30s, the estate owner put in a land drainage scheme in Achnaha and neighbouring Glendrian. You'll still be able to see the patterns of rig and furrow if you keep an eye out.

We build our houses clustered together, weaving the walls from freshly cut wood (like a basket) and lining them with turf, under a thatched roof. We live alongside rival clans and some of us fought on different sides of the Jacobite Uprising in 1715. You know what they say - keep your friends close and your enemies closer!

Go to Achnaha

Fascadale Ice House

The land is farmed all along the coast from here to Achateny, but this is the best place to catch the Salmon when the river is in spate - it's a rare treat to have fresh salmon on the table

Go to Fascadale Ice House

Camas nan Geall

We clanspeople have a strong connection to this land, it goes back generations; an ancient lineage! Clan Cambell buried their dead here. This is a busy spot for the living too: There are crops, and extensive common grazings - as far as Loch Mudle - are used for summer pastures. The settlement contributes to the upkeep of the MacIain Chief and staff, and provides men for the Clan’s army in times of war.

Go to Camas nan Geall

Glendrian

In 1619 the ‘Glendreane’ tenant, Allester McEan Voir VcEan - one of the MacIains - was involved in a clan dispute against Donald Campbell of Barbreck, during which Mingary Castle was besieged!

There were six families living in Glendrian in 1737, a total population of 29 comprising six men, eight women and fifteen children. Our land covers 2,220 acres, which is a lot compared to other settlements around here. Tenants are permitted to graze up to 48 cows, 16 horses and 48 sheep.

Go to Glendrian

Kilchoan Old Parish Church

It was difficult to contain our excitement in church and we think the minister, Lachlan Campbell, might have suspected something. He was against our Jacobite cause and the last person we would want to know about the important passenger who had landed at Loch-nam-Uamh in a French ship. Word got out though and a message made its way to the Duke of Argyll in Inverary.

The ministers are appointed by the Laird and are not always welcomed by the people. I heard that when Duncan MacCalman arrived in 1627 the congregation consisted only of his family and the Church Officer. But the minister joined in with games of putt the stone - and because he was really good, locals came to like him and in time, the Church was full again.

When you visit take a look at the Maclain grave slabs, the two oldest grave slabs in the cemetery dating from the 14th or 15th century, you can see intricate carvings in the Iona School style, and they show the Birlinn symbol of Clan MacIain and a claymore - claidheamh mòr “great sword”.

Go to Kilchoan Old Parish Church

Eviction and Emigration

1746 - 1860

Between about 1750 and about 1880, large numbers of Scottish Highlanders and Islanders were displaced from the traditional lands their families had occupied for generations. Many ended up in coastal settlements with difficult farmland, and others were forced to move away from the highlands, sometimes seasonally, taking jobs in central Scotland's rapidly growing industrial cities. Others emigrated in search of a better life overseas, as far as Australia, New Zealand and North America.

In the early 1800s, the Ardnamurchan Estate was owned by Sir James Riddell. The estate was losing money, so Riddell commissioned a report on how its land was used, with the aim of repairing the financial problems by making the land more profitable. The report advocated that land occupied by poor tenants should be used for sheep farming. Showing little pity for the tenants, the first wave of forced evictions occurred in 1828, when the settlements of Camas nan Geall, Tornamona, Bourblaig, Skinnid and Choiremhuilinn were cleared. Many cleared folk moved to Swordle, walking through snow from the south coast to the north. Others moved to Ormsaigbeg, Acharacle or Glasgow, and some emigrated.

In 1846 the potato famine ravaged crops on Ardnamurchan, which many tenant farmers depended on to be able to pay rent and support their families. Coinciding with this, the price of black cattle, which were driven to market from Ardnamurchan to places like Falkirk, also fell. With tenants unable to pay rent, the Estate was in serious debt, and many tenants on Ardnamurchan were in a state of poverty. Riddell's debts were still rising, and he was forced to move towards selling the estate into private hands. Because of his debts, his creditors appointed trustees to manage the estate, and these were the principal actors in the next wave of clearances across Ardnamurchan. These evictions, beginning in 1852, were often callous; the sick, blind, infirm, widowed, and others who had suffered famine and stock loss were subject to eviction, bankruptcy, removal to another part of the estate, or thrown onto the parish.

To avoid a public outcry at a time when clearances such as these were liable to be reported in the press, the Estate trustee developed local industries such as fishing, wood processing, and lead mining on the estate to offer employment and mitigate the complaints in the press. With this wave of clearances, in which the three Swordles were cleared, the pressure on land became even greater, and areas which were increasingly unsuitable for arable farming were pressed into use. Portuairk which, along with Sanna, had been part of Achosnich common grazings, was designated as a crofting township, and people settled there. People crofted the land and were mostly self-sufficient, but it was a tough life on the coastal settlements and often impossible to make a living from the land alone. Many people left Ardnamurchan for periods of the year to work, for example, in the Police Force in Glasgow or the British Merchant Navy, or had seasonal jobs working for the Estate elsewhere on the peninsula.

In the early 1800s, the Ardnamurchan Estate was owned by Sir James Riddell. The estate was losing money, so Riddell commissioned a report on how its land was used, with the aim of repairing the financial problems by making the land more profitable. The report advocated that land occupied by poor tenants should be used for sheep farming. Showing little pity for the tenants, the first wave of forced evictions occurred in 1828, when the settlements of Camas nan Geall, Tornamona, Bourblaig, Skinnid and Choiremhuilinn were cleared. Many cleared folk moved to Swordle, walking through snow from the south coast to the north. Others moved to Ormsaigbeg, Acharacle or Glasgow, and some emigrated.

In 1846 the potato famine ravaged crops on Ardnamurchan, which many tenant farmers depended on to be able to pay rent and support their families. Coinciding with this, the price of black cattle, which were driven to market from Ardnamurchan to places like Falkirk, also fell. With tenants unable to pay rent, the Estate was in serious debt, and many tenants on Ardnamurchan were in a state of poverty. Riddell's debts were still rising, and he was forced to move towards selling the estate into private hands. Because of his debts, his creditors appointed trustees to manage the estate, and these were the principal actors in the next wave of clearances across Ardnamurchan. These evictions, beginning in 1852, were often callous; the sick, blind, infirm, widowed, and others who had suffered famine and stock loss were subject to eviction, bankruptcy, removal to another part of the estate, or thrown onto the parish.

To avoid a public outcry at a time when clearances such as these were liable to be reported in the press, the Estate trustee developed local industries such as fishing, wood processing, and lead mining on the estate to offer employment and mitigate the complaints in the press. With this wave of clearances, in which the three Swordles were cleared, the pressure on land became even greater, and areas which were increasingly unsuitable for arable farming were pressed into use. Portuairk which, along with Sanna, had been part of Achosnich common grazings, was designated as a crofting township, and people settled there. People crofted the land and were mostly self-sufficient, but it was a tough life on the coastal settlements and often impossible to make a living from the land alone. Many people left Ardnamurchan for periods of the year to work, for example, in the Police Force in Glasgow or the British Merchant Navy, or had seasonal jobs working for the Estate elsewhere on the peninsula.

Meet Eilidh...

A crofter living and working in Sanna, her family had lived for generations in Bourblaig, on the slopes of Ben Hiant near Camas nan Geall, but in 1828 they were evicted and forced to start a new life in Swordle. They lived and worked there for 23 years before Eilidh and many others were evicted from the homes they had built in Swordle and again had to move across the peninsula, this time to Achnaha and then on to Sanna a few years later. It's a tough place to live, and Eilidh runs the household, the croft, and keeps the family afloat. She is responsible for crofting their land in Sanna while her dad works in the Estate fisheries. The land is of poor quality and brings in a meagre income, not enough to sustain a family for long, so her brother works away in the Navy, sending money back to Ardnamurchan when he can. Read her stories below about what life was like during this time.

Read stories told by Eilidh below, and find out what life was like for her …

Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

I watched the boats carrying the granite over to Ardnamurchan point from the Ross of Mull by boat, to build the lighthouse tower. They brought it up to the construction site from the jetty below it. Construction began in 1846, and the lighthouse was completed three years later in 1849 - it was amazing to watch it grow taller! Building the lighthouse was an arduous job though, and it was made even more difficult when scurvy broke out amongst the workers, a doctor had to be called in to treat them.

The lighthouse was struck by lightning in 1852 during a severe storm! The strike smashed glass and shook plaster off the walls of the tower, and outside fifty feet of boundary wall and forty feet of road was knocked down and washed away by the heavy seas.

Go to Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

Fascadale Ice House

The salmon fishery was developed in the first half of the 20th century. Huge numbers of salmon were caught from fishing stations across the peninsula.

Go to Fascadale Ice House

Achnaha

The population here in Achnaha has changed a lot over the years. Some of us that were evicted from our homes in townships further east on the peninsula (like Swordle and Achateny) came to Achnaha. The population swelled in the 1830s, 40s and 50s only to shrink back from the 1860s when people moved out to the new crofting townships of Sanna, Plocaig and Portuairk.

During this time period, parishes sometimes made payments to support those in great financial need. In 1789, the Kirk Sessions recorded one payment awarded to 'a changeling' and their grandmother. At the time, this antiquated term was used to describe a disabled child, and it suggests that the child had been stolen by fairies and replaced with a different child or being - sometimes the fairie’s own child. These kinds of stories were a way for people to make sense of behaviours or differences that they didn’t understand. This record highlights how social attitudes have changed vastly over time.

Go to Achnaha

Camas nan Geall

We were forcibly evicted from our homes as part of the major 'clearance' of the settlements on the slopes of Ben Hiant to make way for a sheep farm. People have had to move to new settlements across the peninsula in search of a new life. Others have emigrated across the ocean, to far away places like New Zealand and Australia.

Go to Camas nan Geall

Glendrian

There used to be many more people living here and we worked the land together. Now we have our own plot of land to work, like in the new crofting townships nearby. It feels very different around here now.

Go to Glendrian

Kilchoan Jetty

The Jetty is on one of the ancient drover routes; along which cattle are moved on foot ("on the hoof") from the Hebrides to cattle markets in Central Scotland and England. Even once they've reached Ardnamurchan from the Hebrides they still have a long way to walk, in all weathers too.

Go to Kilchoan Jetty

Kilchoan Old Parish Church

We heard that the factor, John McColl was so cruel in evicting people from their homes that an old woman cursed him and nothing but weeds now grows on his grave.

Go to Kilchoan Old Parish Church

Sanna

My family and other folk moved to Sanna when we were evicted from the homes we had built - first in Bourblaige, and then Swordle. I hear the whole Swordle area is a large sheep farm now, and it breaks my heart to think of that land being inhabited only by sheep, when it used to be a community of hard working families. It’s been tough to have to start over again, especially here in Sanna, where the land is so difficult to croft. I envy the sheep who have the best of the land now!

Back in 1851 there were only three households here, but ten years on there are 23.

Go to Sanna

Swordle

My family built a new house and a new life when they arrived in Swordle in 1828, after being callously evicted from their home in the settlement of Bourblaig, near Camas nan Geall. We were evicted from Swordle only 23 years after arriving, and took the long journey West to Achnaha and then on to Sanna. Many people I know emigrated to Canada, Australia and New Zealand to seek a better life.

Go to Swordle

Crofting and Fishing

1860 - 2000

From the later nineteenth century, the industries and livelihoods of most people living on Ardnamurchan revolved around crofting and fishing activities. Most of the population lived in coastal crofting townships, with most other land on the peninsula used as sheep farms for the Ardnamurchan Estate. The Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act came into effect in 1886, which ensured security of tenure for the crofters, controlled rents, and produced the first Crofters Commission, a land court which ruled on disputes between landlords and crofters. The act also required the crofters to reside close to their croft and keep it cultivated, maintained and put to good use.

The organisation of crofting means that each family rents their own plot of land, and also has a right to use common grazings for a fixed number of cattle and sheep, known as the 'souming'. The individual plots of land often stay within a family for generations, which is different from earlier ways of organising land, where the plots were common land and rotated between families on a regular timetable.

The displacement of the population to coastal settlements created pressure on the amount of arable land available to sustain families. The crofts were small, and in addition to crofting, tenants had to work for the estate to pay their rent or leave Ardnamurchan to work, for example, in the Glasgow Police Force or the British Merchant Navy. Others worked in the salmon fisheries around Ardnamurchan, the main industry on the peninsula. Once thriving, the salmon fishing industry declined throughout the 20th century due to a constant decrease in salmon numbers, primarily due to industrial overfishing, pollution and the changing climate.

Initially, most crofters' houses were single-storey, hip-roofed, and thatched. They would have two rooms, each with a fireplace and a chimney in the centre of the roof to let out the smoke. Newer houses were gable-ended, with their fires and chimneys against the gable. As time went on, corrugated iron replaced thatched roofs. From the 1930s, an upper storey was often added, and the roof covered with slates or asbestos tiles. Many of these houses are still in use today.

The organisation of crofting means that each family rents their own plot of land, and also has a right to use common grazings for a fixed number of cattle and sheep, known as the 'souming'. The individual plots of land often stay within a family for generations, which is different from earlier ways of organising land, where the plots were common land and rotated between families on a regular timetable.

The displacement of the population to coastal settlements created pressure on the amount of arable land available to sustain families. The crofts were small, and in addition to crofting, tenants had to work for the estate to pay their rent or leave Ardnamurchan to work, for example, in the Glasgow Police Force or the British Merchant Navy. Others worked in the salmon fisheries around Ardnamurchan, the main industry on the peninsula. Once thriving, the salmon fishing industry declined throughout the 20th century due to a constant decrease in salmon numbers, primarily due to industrial overfishing, pollution and the changing climate.

Initially, most crofters' houses were single-storey, hip-roofed, and thatched. They would have two rooms, each with a fireplace and a chimney in the centre of the roof to let out the smoke. Newer houses were gable-ended, with their fires and chimneys against the gable. As time went on, corrugated iron replaced thatched roofs. From the 1930s, an upper storey was often added, and the roof covered with slates or asbestos tiles. Many of these houses are still in use today.

Meet Calum...

He can tell you about the rhythm of life here; family, fishing after a day's work and how the women of Sanna campaigned for a road to be built to their village. He's best friends with the Lighthouse Keeper at Ardnamurchan Point, and knows all about fixing things, from fishing nets to Kilchoan Jetty!

Read stories told by Calum below, and find out what life was like for her …

Achnaha

There's a strong sense of community in Ahnaha, and people often help each other out with farming work. Perhaps this is a throwback to the older style of farming in pre-crofting days, back when people often shared the work on each other's land.

Go to Achnaha

Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

Keeping a lighthouse takes a lot of work. They've got to maintain the essential equipment but also do lots of cleaning, scrubbing, and polishing; the lamp needs to be polished throughout the day. There’s lots of painting to be done too. Large tins of Brunswick Green paint are supplied to the lighthouse, and so everything gets painted that colour; the van, the rabbit hutch… everything matching green.

It was a lighthouse keeper’s job to light the lamp every night and make sure it stays lit until the morning. Before its automation, the lighthouse had a Fresnel lens, which had hundreds of pieces of specially cut glass to reflect and refract light, creating the strong beam of light to guide ships in the night. The lamp rotated with a clockwork mechanism of gradually descending weights, pulleys and gears that the lighthouse keepers set and maintained every day. The stone weights took an hour and a half to descend all the way from the top to the bottom of the lighthouse - sometimes the keepers had time to make a cup of tea while they waited!

The late Queen Elizabeth II used to regularly travel around the lighthouse in the Royal Yacht Britannia. In 1986, she stopped for a visit and had afternoon tea with the lighthouse keepers. This wasn’t a spontaneous encounter - the lighthouse keepers had time to smarten up the lighthouse before the visit and a number of alterations were carried out - including replacing cobbles and improving the kitchen.

The lighthouse keepers and their families are always on the move, it’s part of the job. The first lighthouse keepers to work here were brought in from other areas, and they only usually stay a few years before being assigned to a different lighthouse. There are often generations of lighthouse keepers within the same family too; it must help to grow up understanding the keeper's lifestyle!

In the early days, families living at the lighthouse were mostly self-sufficient. They grew their own food, kept cows and chickens, and fished at the jetty. The house and kitchen had to be kept in good order at all times, as there could be inspections without warning.

Go to Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

Fascadale Ice House

A succession of fishing families from outside Ardnamurchan have leased the salmon fishing rights - at great expense! Locals have seasonal work here, helping with fishing and maintenance, but it’s hard and sometimes dangerous work.

We got an ice machine at the fishery in the 1950s, which is powered by a generator as there wasn’t electricity in Fascadale until the 1960s. It certainly saves on manual labour, it was hard work making ice the traditional way!

The salmon hauls certainly seem to be getting smaller and smaller in recent years - I can still remember huge numbers of fish filling up the floor of the boat! It hasn’t been like that for years now, and I don’t think commercial fishing will be economically viable here for much longer. There are many reasons for the decline of wild salmon numbers; industrial overfishing, pollution and the warmer winter being key factors.

The salmon are cleaned to get rid of lice but I always leave some on purpose - buyers can’t deny it’s fresh fish when it arrives with a few lice! It can get pretty cold out there, so when we return to Fascadale with the day’s catch, we warm up by lighting a fire in the packing shed (where the Coble is now housed).

The actual practice of salmon fishing hasn’t changed much over the years. We fix bag nets along the shore, going all the way back to Dorlin. To get the net in position the salmon boat, called a coble, has to work herself right into the rocky shore - a scary business along the exposed shores, particularly out towards the lighthouse. To empty out the salmon into the boat we need to plunge our arms into the nets... but there are often jellyfish in there too, and many painful stings are sustained. One time taking in leaders I got so jellyfished, I felt ill and had to go home to bed. I hear people have started to use synthetic nets, which will make the job a little - but not much - easier.

Go to Fascadale Ice House

Kilchoan Jetty

Salmon on the West Coast of Scotland are caught in nets known as bag nets. We change the nets every week, pulling the old one ashore to be cleaned and mended. Mending the nets is a skill that requires a lot of patience, a sharp knife, and the ability to wield a “net needle”. And then there’s the language of “three leggers” and “two leggers” that has to be understood before a hole can be properly mended.

At the end of the day when our work is done, the other crofters and I head down to the jetty and go out fishing to catch lobsters, crabs and fish for ourselves. You just catch what you need for a couple of days, since there isn’t a way to freeze them in our homes. We’re all good seamen and we all look forward to competing in the Regatta - most of us are in lug sail boats with just one sail, but they can go alright! Everyone comes to Kilchoan for the Regatta, all the way from the other side of the peninsula and from Tobermory, it’s my favourite day of the year!

The folk who have the shop have a motor launch that’s always going in and out of the jetty to bring in goods for the shop and to take people out to the big ferry. Folk gather in front of the shop while they are waiting to be taken out to the big ferry.

We catch the ferry from Kilchoan to Tobermory, and out to the passing MacBrayne ferries when travelling further afield. If a passenger is local sometimes they can travel for free, although once a visitor got in a huff when he saw this happen and refused to pay his fare! The ferryman was outraged and sent him a letter that read “give me my tuppence”... I heard he's still waiting for a reply.

We fish at six nets from Kilchoan: the most westerly, “Jib and Lug” being half way between Kilchoan and Ardnamurchan Point, and the most easterly being “MacLeans Nose” at the mouth of Loch Sunart. In between there is “Rhubha na Gall”, “The Twins”, “The Pier Net” and “Mhile Burn”.

Working the boat and the nets is easier at Kilchoan than at Fascadale. The old jetty was rebuilt over the winter of 1982 by local volunteer labour, and it’s a very useful landing place for dirty nets coming ashore and clean nets to be loaded onto the boat. Fortunately the jetty is just wide enough to wheel a trailer down to the boat and then tow it back up and onto the green. A task that takes a crew of four at Fascadale can be managed by two people in Kilchoan.

Go to Kilchoan Jetty

Sanna

We finally got a road to Sanna in 1925 - the women of Sanna and Plocaig led the campaign and petitioned Queen Mary. Before the road was built, goods for the village were carried all the way from Achnaha, and coffins had to be carried that way too.

A resident of Sanna you may have heard of is the photographer and writer MEM Donaldson. She travelled extensively through Scotland, and her work shows everyday lives of Ardnamurchan residents of the time.

Now a private dwelling, photographer and writer MEM Donaldson lived at Sanna Bheag, a dwelling built with local materials and labour. A fire in 1947 damaged the building, the cause of which is still a mystery. Thankfully, MEM Donaldson’s work survived the fire, and remains an archive that captures her experience of life in the 20th century Highlands. You can find out more about her life here: https://www.highlifehighland.com/inverness-museum-and-art-gallery/m-e-m-donaldson/

The writer Alasdair MacLean writes about his childhood on the family croft at Sanna in his book, Night Falls on Ardnamurchan. It details the daily tasks of life crofting in Sanna, and gives an insight into crofting life at the time.

Go to Sanna

Camas nan Geall

I heard the local factor moved into Camas nan Geall after families were forcibly evicted to make way for a sheep farm. One of the 18th century houses was made bigger and a little grander, including an elaborate cobble floor.

Go to Camas nan Geall

Glendrian

Farming was a way of life here, but over the years there were huge changes in the types of farming and the ways the buildings around here were used. The lack of road connection makes things even more difficult, and the population slowly but surely shrank over the years. By the late 1930s there were only two families living in Glendrian, and in the 1940s the village was deserted when the last occupant left to stay with her nephew in Achnaha. As the number of households declined, the uninhabited buildings were made use of by the remaining occupants. They blocked windows and hearths to make byres and stores, and used stone to form animal enclosures. One house was even used as a garage. The last two houses used as dwellings were made much grander and more comfortable with drainage, mortared and rendered walls. One of them had a second storey added too.

Go to Glendrian

21st Century

2000 onwards

Although the population of Ardnamurchan is lower compared to the past, the community here is still dynamic and active; regularly organising events, activities and initiatives for locals and visitors alike. The annual West Ardnamurchan Regatta is highly anticipated every summer, and people travel far and wide to join, gathering in Kilchoan to compete on the water and then ceilidh together in the Community Centre.

The beautiful landscape and the peninsula's remote setting attract many visitors in the summer months, and many traditional crofting cottages have been transformed into holiday cottages. However, the crofting tradition is still very much alive on Ardnamurchan, with crofts in use today that have been in the same family for generations. Respect for the land and inherited knowledge is visible in the continued use of traditional farming methods, such as using seaweed gathered from the shore to fertilise fields.

West Ardnamurchan is renowned for its wildlife, flora and fauna, with eagles, deer, pine martens, seals, dolphins, and even minke whales to be spotted. Ardnamurchan Lighthouse, which is now owned by the community, is a popular destination and offers fascinating tours during the warmer months of the year. Today, some people travel to the peninsula from Australia to reconnect with the homeland of their ancestors who sailed away many years ago.

Ardnamurchan has been inhabited for over 6,000 years and has a rich and diverse history. For a seemingly remote place, it has connections to locations around the world through the comings and goings of people, culture, and trade throughout history. Projects and work carried out by Archaeology Scotland, students and staff from the Universities of Manchester and Leicester, as well as local people and community groups, are continuing to reveal its archaeological and historical significance. Many sites of historical importance have been discovered and excavated, and there are still many layers of history to uncover to understand the past and how it has shaped West Ardnamurchan as we know it today.

The beautiful landscape and the peninsula's remote setting attract many visitors in the summer months, and many traditional crofting cottages have been transformed into holiday cottages. However, the crofting tradition is still very much alive on Ardnamurchan, with crofts in use today that have been in the same family for generations. Respect for the land and inherited knowledge is visible in the continued use of traditional farming methods, such as using seaweed gathered from the shore to fertilise fields.

West Ardnamurchan is renowned for its wildlife, flora and fauna, with eagles, deer, pine martens, seals, dolphins, and even minke whales to be spotted. Ardnamurchan Lighthouse, which is now owned by the community, is a popular destination and offers fascinating tours during the warmer months of the year. Today, some people travel to the peninsula from Australia to reconnect with the homeland of their ancestors who sailed away many years ago.

Ardnamurchan has been inhabited for over 6,000 years and has a rich and diverse history. For a seemingly remote place, it has connections to locations around the world through the comings and goings of people, culture, and trade throughout history. Projects and work carried out by Archaeology Scotland, students and staff from the Universities of Manchester and Leicester, as well as local people and community groups, are continuing to reveal its archaeological and historical significance. Many sites of historical importance have been discovered and excavated, and there are still many layers of history to uncover to understand the past and how it has shaped West Ardnamurchan as we know it today.

Meet Màiri...

She is here to tell you about life in West Ardnamurchan since the millennium. She has witnessed the community coming together in many different ways; repairing Kilchoan Jetty, bringing the Lighthouse into community ownership, and joining archaeological digs. She'll also share her favourite spots for wildlife spotting and watching the sunset!

Read stories told by Màiri below, and find out what life was like for her …

Achnaha

Achnaha is in the middle of an extinct 65 million year old volcano. To the north, you can see the edges of what is left of the crater. Achnaha has been a crofting community for generations, and the land continues to be crofted today.

Go to Achnaha

Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

The light that shines from the lighthouse is now controlled from Edinburgh. Ardnamurchan Point features in the daily shipping forecast, between the Mull of Kintyre and Cape Wrath.

On a clear day, this is a wonderful place to watch the sun go down. Take a seat on one of the rocks, and watch the sky fill with fiery and vibrant colours as the sun slowly descends below the horizon.

Go to Ardnamurchan Lighthouse

Glendrian

The mixed farming with arable crops and animals slowly became more orientated towards sheep farming, and today Glendrian is a peaceful spot with sheep grazing around the ruins of the old buildings. The memory of arable farming is still present with the rig and furrow patterns visible on the land all around the settlement; some of these were ploughed by horses years ago.

Go to Glendrian

Kilchoan Jetty

My friend had a temporary job working on the jetty refurbishment in about 1998. When he worked on it again as a volunteer in 2020, he was pleased to see that the work he had done 22 years ago still looked good. It looks like the work they’ve just done should last for many years too!

Net fishing was practised from the early 1800s and continued in Kilchoan until the 21st century - that’s a lot of salmon! Very few salmon were caught in later years however, and net fishing was prohibited in 2016 to tackle overfishing.

She was a big, heavy, and very capable vessel, “Iolair”, and is said to be the first fibreglass coble built in Scotland. Bought new in 1975 by the Fascadale Fishery, she was subsequently used by a local man who had worked at Fascadale many years previously, and used to fish at Kilchoan until the 2016 European ban on coastal netting was introduced to protect Atlantic salmon stocks.

Go to Kilchoan Jetty

Sanna

Sanna is known for its variety of stunning coastal scenery, and today is popular with tourists and locals alike who come here to enjoy the white beaches, turquoise waters, rockpools, and views of Ardnamurchan Point and The Small Isles. I encourage visitors to leave the beach as they found it and be mindful of the local wildlife.

Go to Sanna

Swordle

Archaeologists are uncovering the rich tapestry of history present at this bay, and alongside community groups they have made many exciting discoveries in recent years. Ardnamurchan is a place with many stories still waiting to be told!

Isotopic analysis allows us to understand where a person grew up due to the chemical signatures in their bones. Although only two teeth survive of the person buried in the viking boat burial, archaeologists are able to deduce from the analysis that he came from coastal Norway.

Go to Swordle